# Creating and Linking Targets

Table of Contents

Article Goals

In this article, we will look into more development topics of CMake and examine the CMake language in depth. We will take a look at the CMake documentation, and understand some key concepts which includes targets for other objects to use and consume them. We will discover how to create them, use them, and add properties to targets. For example, targets have scope information, and the scope of these targets effects how other targets consume and use them.

Then we will look into a real example with CMake using a command line program.

Article’s Scope

We will look into the some key concepts:

- dig deeper into the the three basic commands a CMakeLists.txt must contain by looking into the documentation.

- creating targets (a library) from an executable to consume and use it in our program

- how different scopes (public, private, and interface) keywords effect the library during the build

- how to link the library to the main program

- see how a dependencies graphs aids in target/dependency development

- how to build just a single target, if you have many targets

- see an example program with a created library and see it run

Prerequisites

Getting familiar to Article #1 helps. Give it a look if you haven’t already.

CMake Minimum Requirements

We will look into the three basic commands that are necessary for the root CMakelists.txt to contain. These commands are needed somewhere in the project, however they can be somewhere within the cascading subdirectories of CMakeLists.txt. We will see that “add_executable” command will be in another CMakeLists.txt in the tutorials example.

Now what are the minimum commands for CMake? In the last article, we saw them in the simple executable example. We’re going to reexamine them more in-depth.

Lets summarize what these command are supposed to do at a high level then look at the documentation.

- cmake_minimum_required — allows the project to establish what CMake VERSION the script depends on.

- project — names the CMake project and allows to reference the project.

- add_executable — names the executable and allows to reference the executable.

Reading CMake Documentation

CMake conveniently documentation gives us the ability to look up what these commands need as inputs and elaborates what the overall command does. As a new CMake developer, it can be confusing what everything means; however for newer CMake users, the generalized command example guides us how to use the given command properly.

When reading the example commands, notice the punctuation and syntax of the command. The punctuation marks between the parentheses (”()”) provides all the inputs needed but some of them can be optional. For example, anything that’s capitalize must be written as-is, because it sets some CMake variables internally. Other than the capitalization, the less than and greater than (”<>”) symbols requires a user input value to be as a parameter. Anything with square brackets (”[]”) is considered optional with everything in between the brackets to be written as as-is and replace any ”<>” variables, of course.

Lets take a look at specifically to the three basic CMake command’s documentation.

cmake_minimum_required()

The example commands from the cmake_minimum_required documentation:

$ cmake_minimum_required(VERSION <min>[...<policy_max>] [FATAL_ERROR])As we can see VERSION keyword is required with an input (<min>) and everything else between the square brackets as optional. Just like previously stated, inside the square bracket must be exactly followed. With the particular option <policy_max>, gives us a range for the minimum and maximum value for the CMake version or it will throw an error.

Lets give an example.

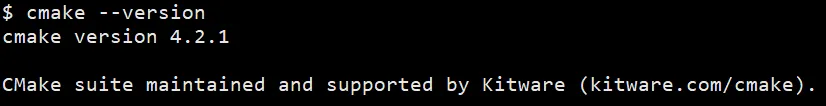

To figure out the version of the current CMake you’re one, open up your favorite command line and type in “cmake —version”. For example, my version happens to be version 4.2.

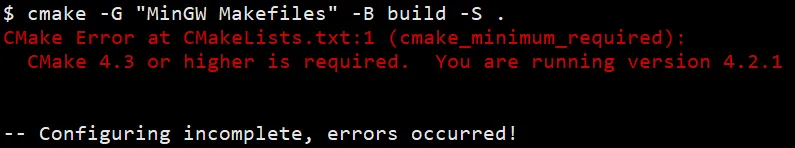

Lets add the FATAL_ERROR option as well, so if your CMake’s version is less than 4.3, CMake will stop the configuration/generation/build stage and thrown an error to the command line.

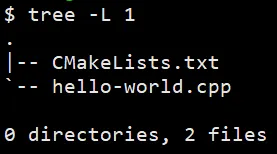

To illustrate this error, lets set up a file structure something like this, exactly like article #1.

Add the contents to the files below:

cmake_minimum_required(VERSION 4.3 FATAL_ERROR) // will throw an errorproject(Tutorial)add_executable(hello hello-world.cpp)#include <cstdio>#include <cstdlib> // EXIT_SUCCESS

int main(){ std::printf("Hello World\n"); return EXIT_SUCCESS;}Now, lets put the command as follows:

$ cmake -G "MinGW Makefiles" -B build -S .Just like that, CMake will yell at you as expected!

Change back the version number to 4.2 for the error to cease.

project()

The example commands from the project documentation:

# option #1$ project(<PROJECT-NAME> [<language-name>...])

# option #2$ project(<PROJECT-NAME> [VERSION <major>[.<minor>[.<patch>[.<tweak>]]]] [COMPAT_VERSION <major>[.<minor>[.<patch>[.<tweak>]]]] [SPDX_LICENSE <license-string>] [DESCRIPTION <description-string>] [HOMEPAGE_URL <url-string>] [LANGUAGES <language-name>...])As we can see, there’s two different forms of the acceptable project() commands. Option #1 is more compact and less complex than then option #2, and depending on the complexity of the CMake script, adding all of the optional values might be needed. However for this example, that isn’t necessary, since we don’t need to add more details to the project.

We will use the simple version, and in the documentation, add the “CXX” as the language to add more detail to our project. Adding this detail acknowledges CMake to look for compilers and/or toolchains for the C++ language. Once again, this is optional but it’s good to have these details in the project.

add_executable()

The example commands from the add_executable documentation:

# option #1$ add_executable(<name> [<options>...] [<sources>...]) # normal version

# option #2$ add_executable(<name> IMPORTED [GLOBAL]) # imported version

# option #3$ add_executable(<name> ALIAS <target>) # alias versionThere are multiple versions used for different types of executables, however we aren’t interested in option #2 or #3. However, lets introduce a brief explanation of and IMPORTED and ALIAS keywords:

- IMPORTED allows to connect an external executables, like another development tools, into your project

- ALIAS allows to rename any executable — simply gives it a new name

Now back to option #1, the add executable commands makes a target, and the name of the target is set by the <name> value. The <sources> input adds any .cpp files initially to the target, and add as many files as you want. However we will see creating a library simplifies a massive list of .cpp files.

# example #1 -- empty executableadd_executable(myProgram)

# example #2 -- executable with sources files addedadd_executable(myProgram math.cpp logs.cpp)Example #1 just creates an empty target named “myProgram”. However in Example #2, an executable created by packaging math.cpp and logs.cpp into the target executable. We don’t need to discretely add .h or .hpp files in the [<sources>…] option of the command, since they are reference in the .cpp with an #include directive.

Creating Targets

On the first look, we’ve seen what are the minimum command for basic CMake script. Similarly just like the add_executable command, there’s a set of commands that help developers to create targets. Targets help support abstracting away potential complexities into one entity.

Some of the most common commands creating CMake targets and generally, they have very similar documentation syntax:

When you make a target, it gets named, and CMake understands to create an object or, in CMake verbiage, an artifacts. CMake refers to artifacts in a more general term than libraries, headers, or objects to name a few.

The add_executable and add_library commands create a target, which is a key concept in CMake development.

Adding Files to Targets

However, just because you make a target doesn’t mean anything is associated with it — assuming you didn’t use the <sources> option in the add_executable command. Think of targets as an empty vessel or shell, and “target_source” (and similar commands) weave together translation units (cpp files) into the artifact(s).

Some commands add translation units (cpp files) to targets and target_sources is one of them.

Like we’ve seen in #### add_executable() section, Example #1 creates an empty target with no source files. Using the target_sources command, it effectively comparable to Example #2.

# creating an empty targetadd_executable(myProgram)

# adding source files with scope to target (executable)target_sources(myProgram PRIVATE math.cpp logs.cpp)As we see, there’s a scoping keyword (PRIVATE) used. Let’s take a look at what that means.

Target Visibility

Introducing targets means now we’re introducing the topic of scoping targets. Target scoping determines what’s visibility relationships between the source target and other target consumers. In other words, it’s a mechanism to help with managing dependencies.

Think of scoping similar functionality to C++ class scopes — like how it defines how other targets will “see” the relationships between two targets.

However unlike C++ class scoping, CMake target visibility help pass characteristics to other targets or just reading the given target’s characteristics. These command help propagates information between the two targets. This is when a relationship is created between targets.

There are three different target visibility keywords:

- Private — will not propagate its dependencies to other targets it consumes

- Interface — will only propagate as a dependency to other targets consuming it

- Public — will propagate as a dependency to any other targets consuming it

Scoping is more of a complicated topic, as there isn’t any correct answer when to use one over the other. After some experience, hiding target information aids better development.

To help with property propagation understanding, following table assist what keyword to scope your targets:

| Target | Others | |

|---|---|---|

| YES | NO | |

| YES | PUBLIC | PRIVATE |

| NO | INTERFACE | - |

You can think of it as — PRIVATE is for me, INTERFACE is for others, PUBLIC is for all of us.

Setting/Getting Properties from Targets

When you link targets together, their properties are consumed, shared, or given to between the visibility relationship they have. Some properties are specific to that target (for example executable or library) and depend on the target type, however we are allowed to make our own personal properties as well.

Target specific properties:

Costume properties:

Just hinting at this topic because we will look into it later. Take notice properties can be read, written, and you can create your own target properties as well.

Linking Targets to Each Other

Now we have an source filled artifact floating in CMake space, we now need to link that library to something — in our case — an executable to consume. This is when target_link_libraries command comes to the rescue.

- target_link_libraries — connects and links specific target together and their relationship is related to the scope keyword used

# non-empty executable createdadd_executable(myProgram math.cpp logs.cpp)

# non-empty library createdadd_library(myLib PRIVATE scientific-math.cpp)

# connecting myLib library to executable as a dependencytarget_link_libraries(myProgram PRIVATE myLib)We can see the library we created is now being consumed by the executables, so any library functions in myLib can be used by myProgram.

Using CMake to Build a Specific Target

When you type in “cmake —build build”, CMake builds everything in the CMakeLists.txt script. However, lets say we have a complicated target, and you might what to debug just that target? Luckily, CMake allows to create a specific target in you project.

For the building stage, add the “—target” flag/option, it will look something like this:

$ cmake --build build --target <target-name>Example Code

We’ve seen how to create targets, adding source files to targets, looked at CMake scoping of targets, and linking targets to each other. That’s all well and great, but lets see a real example and how all the commands interact with each other. I want to emphasize on the CMakeLists.txt and not the source code itself, however feel free to examine all the code in the repository.

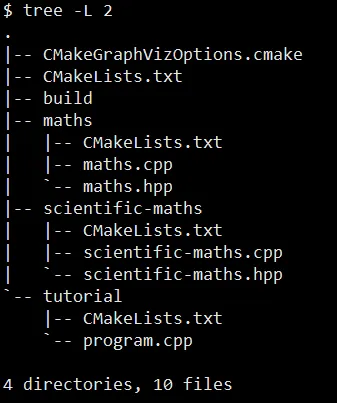

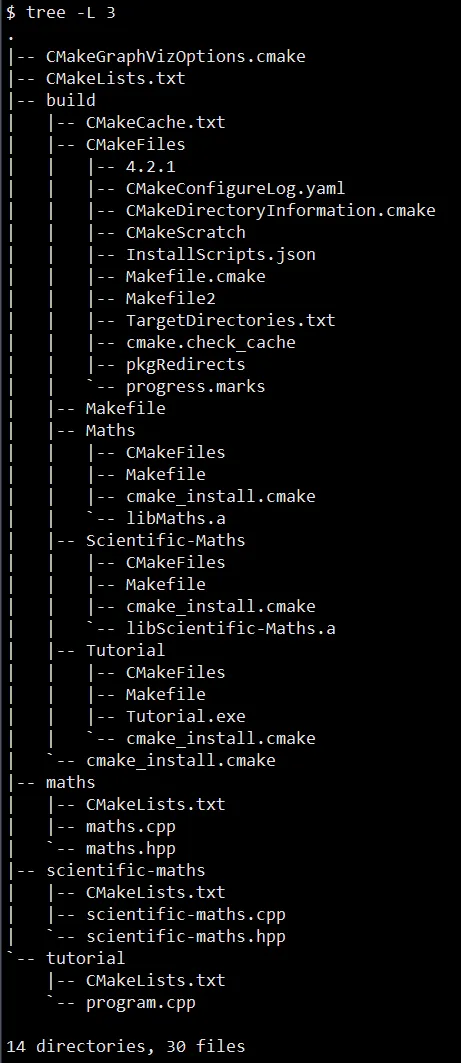

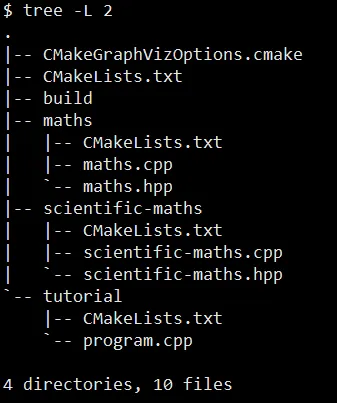

By cloning the repository, then going into the ‘2-creating-and-linking-targets/project-example’ repository, the file structure should look like this:

Lets configure and build this project:

$ cmake -G "MinGW Makefiles" -B build -S .$ cmake --build buildOnce the commands are executated we can see a file structure similar to this:

As we can see in the “Example Project — Build File Structure” diagram, the subdirectories called “build/Maths”, “build/Scientific-Maths”, and “build/Tutorial” all contain build artifacts from the CMake commands. “build/Maths” and “build/Scientific-Maths” both created a file with a “.a” extension which is static library. We will talk more about static libraries later in the series, but for now just acknowledge it’s a library. Of course, “build/Tutorial” created a “.exe” file or an executable for specifically for a Windows OS — Depending on the OS, you’re executable will show a different files extension type.

Analyzing the Project’s CMakeLists.txt

Lets peek into how CMake produces these targets, and let’s peruse through each target’s subdirectory CMakeLists.txt.

# establishes the minimum CMake version (4.2) this script depends on# and will throw an fatal error otherwisecmake_minimum_required(VERSION 4.2 FATAL_ERROR)

# names c++ as the project's language as well as naming the project "Tutorial"project(Tutorial LANGUAGES CXX)

# creating a directory structure in the build folder# it will create empty folders named "Tutorial", "Maths", and "Scientific-Maths"add_subdirectory(Tutorial)add_subdirectory(Maths)add_subdirectory(Scientific-Maths)# creating an empty target named "Scientific-Maths"add_library(Scientific-Maths)

# adding associated files to target# add scoped sources (scientific-maths.cpp and scientific-maths.hpp) to a target called "Scientific-Maths"target_sources(Scientific-Maths PRIVATE scientific-maths.cpp PUBLIC FILE_SET HEADERS BASE_DIRS . FILES scientific-maths.hpp)# creating a target empty target named "Maths"add_library(Maths)

# adding associated files to target# add scoped sources (maths.cpp and maths.hpp) to a target called "Maths"target_sources(Maths PRIVATE maths.cpp PUBLIC FILE_SET HEADERS BASE_DIRS . FILES maths.hpp)# creating an empty executable targetadd_executable(Tutorial)

# adding files (program.cpp) to previously created executable called "Tutorial"target_sources(Tutorial PRIVATE program.cpp)

# connecting other libraries created in other subdirectories to main program called "Tutorial"target_link_libraries(Tutorial PUBLIC Maths PRIVATE Scientific-Maths)Visualization of Dependencies

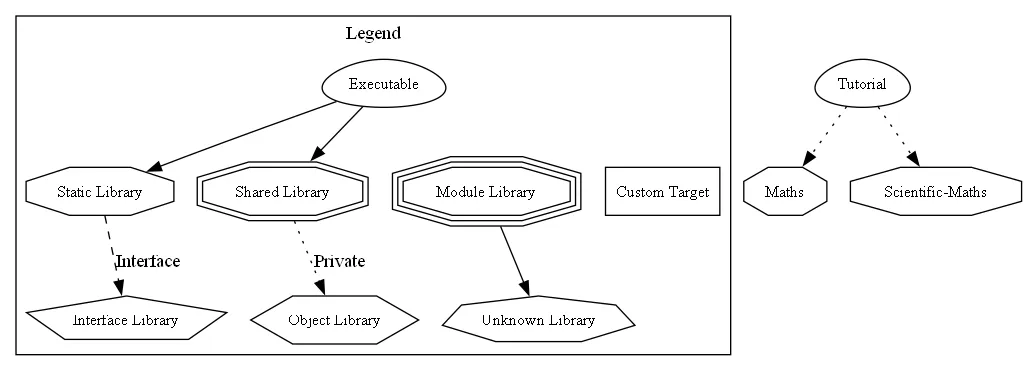

Now suppose we are given a project with a lot of targets creating a giant web of dependencies between the executables and the targets. It might not be obvious or clear how everything fits together, however CMake contains an internal tool called Graphviz to help with documentation. For creating a dependency graph for better documentation is easier then ever.

I would suggest generate the dependency documentation inside the build directory, so you don’t mixup source code and build artifacts. This idea is called out-of-source build.

Graphviz Setup — Process Script Mode

In order to use the graphviz feature, we have to create a special configuration file called “CMakeGraphVizOptions.cmake”.

Inside the fill add the following:

message("")message("GRAPHVIZ option(s) confirmed")message("")

set(GRAPHVIZ_CUSTOM_TARGET TRUE)As we can see, this file isn’t anything similar to other CMake scripts we’ve created before. First off, it doesn’t have a .txt file extension but a .cmake. This tells CMake it’s a configuration file, and it doesn’t have to follow general CMake rules like including a “project()” command inside the file. However, we can see it’s named a particular way, and it must be called “CMakeGraphVizOptions.cmake” exactly. CMake looks at the Graphviz dependency and checks how Graphviz files should be configured.

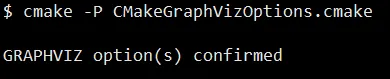

Anytime CMake see a “—graphviz” flag/option, CMake will look into the source tree and run the “CMakeGraphVizOptions.cmake” script automatically. However, you call just run the script all by itself by using the “-P” like so:

$ cmake -P CmakeGraphVizOptions.cmakeGive it a try, it should look something like this:

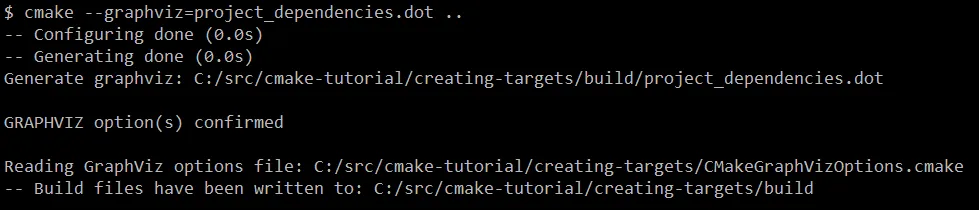

Creating the Dependency Graph

Now lets start generating the library dependency graph, use the commands to product a Graphviz dependency graph:

$ cd build# creating a .dot file$ cmake --graphviz=project_dependencies.dot ..# producing a .png from the .dot file$ dot -Tpng project_dependencies.dot -o project_dependencies.png

Since we used the “—graphviz” flag, the “CMakeGraphVizOptions.cmake” script also ran as we can see it in the output above! Ain’t that neat?

Opening up the .png file, we can see something very similar to this!

Resources

Modern CMake for C++ by Rafał Świdziński